UAV LiDAR mapping under forest to find Iron Age Roman archaeological remains in the South of France

Mapping forested archaeological sites using UAV LiDAR: the example of the site “L’Escalère” in the South of France.

Since 2016, the UMR 5608 TRACES Lab Research team uses YellowScan LiDAR (Mapper and then Mapper 2) to scan archaeological sites under forest cover. This time, the Toulouse-based research team flew their Mapper 2 on a DJI M600 over “L’Escalère” site near Saint-Martory in Garonne river valley in the South of France.

The mission objective was to map micro-reliefs of archaeological interest on a hillfort known to have hosted pre-Roman and Roman human occupations, now covered by forest. Preserved 1m to 2m high dry stone walls were already known to be there, and precise mapping of the structures was necessary for archaeological excavations. The aim was to obtain digital 3D data in the shortest time possible in the field with the flexibility offered by Drone LiDAR mapping.

YellowScan Mapper 2 and DJI Matrice 600 UAV before take-off in “L’Escalère” archaeological site – Photo credit. Nicolas Poirier.

YellowScan Mapper 2 and DJI Matrice 600 UAV taking off in “L’Escalère” archaeological site – Photo credit. Nicolas Poirier.

“The area surveyed was 17 hectares large and the mission lasted a week: 1 day for planning, 1 day for acquisition and 3 days for data processing” reported Nicolas Poirier, researcher at UMR 5608-TRACES and UAV pilot.

Only 3 flights (10-12 minutes) were necessary according to the team with the Mapper II UAV LiDAR system capturing data while being flown at 50 m AGL and 4 m/s speed.

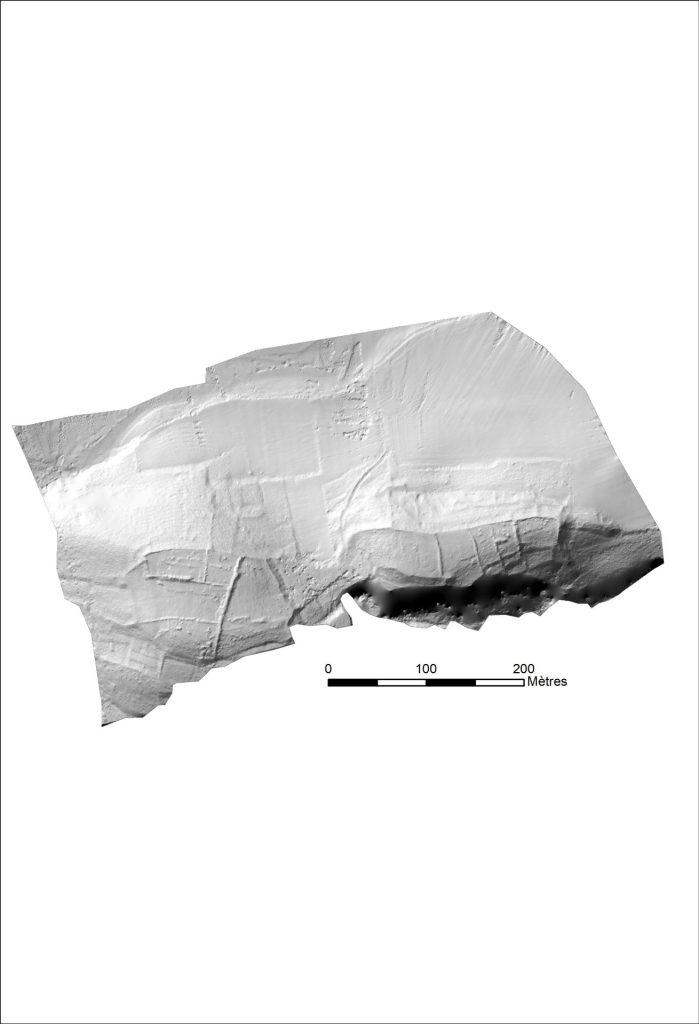

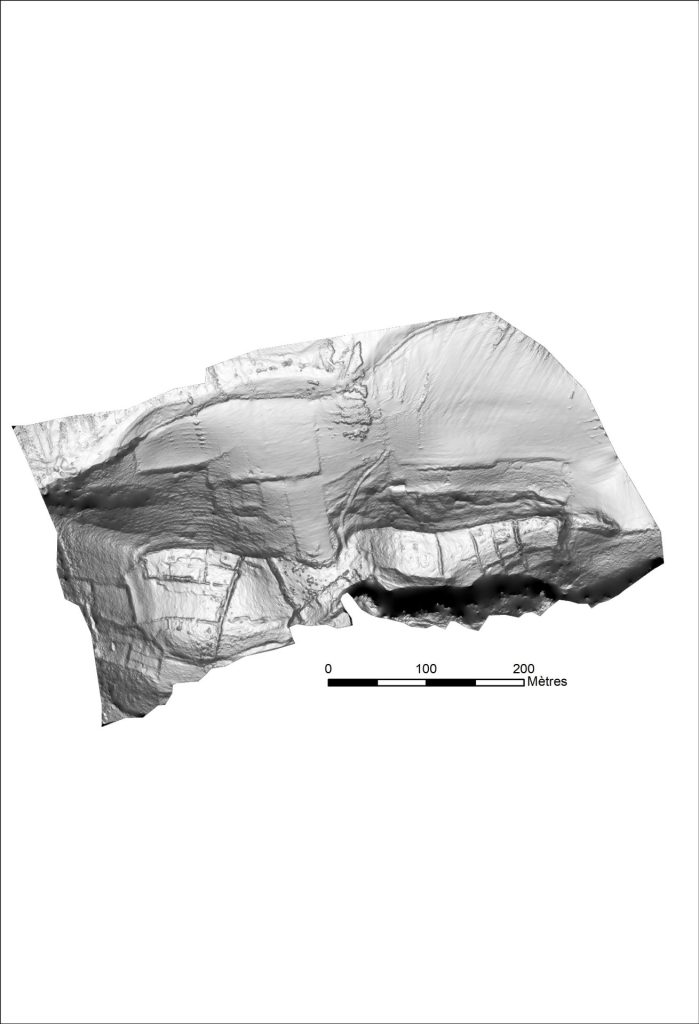

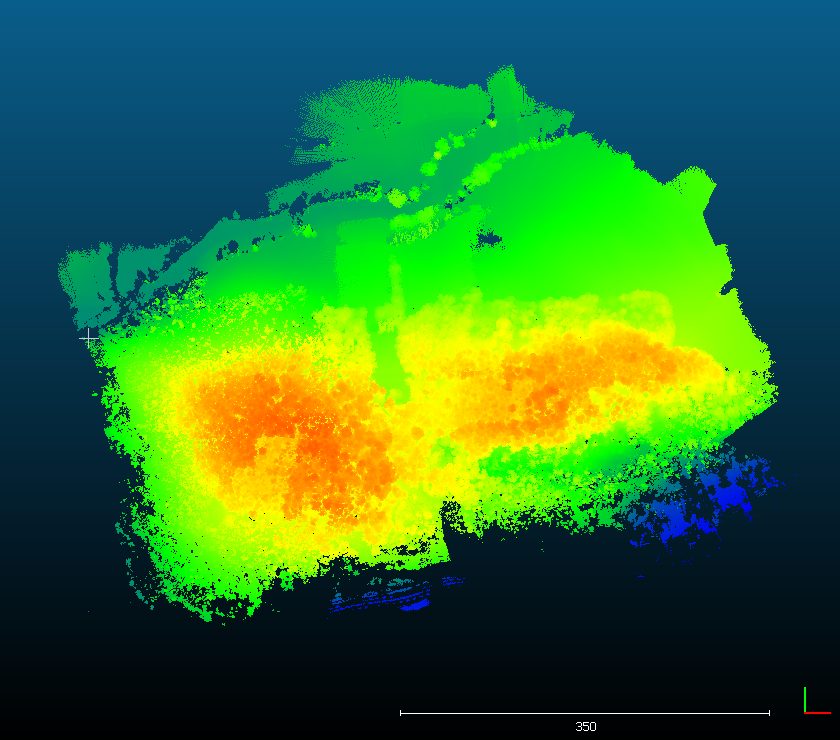

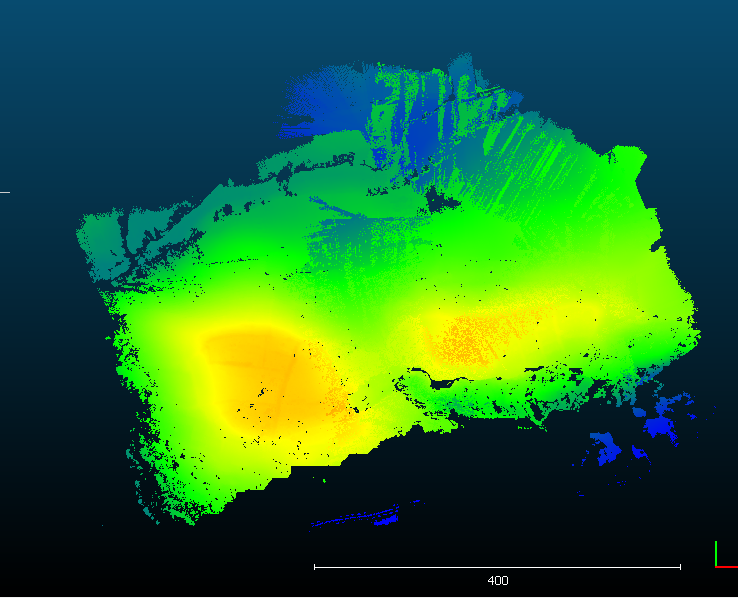

Results: The LiDAR pointcloud generated showed a +120 pts/m² and a 1 to 2cm accuracy after PPK post-processing. Digital Terrain Models visualizations were created using Relief Visualization Toolbox and anomalies were vectorized using ArcGIS 10.

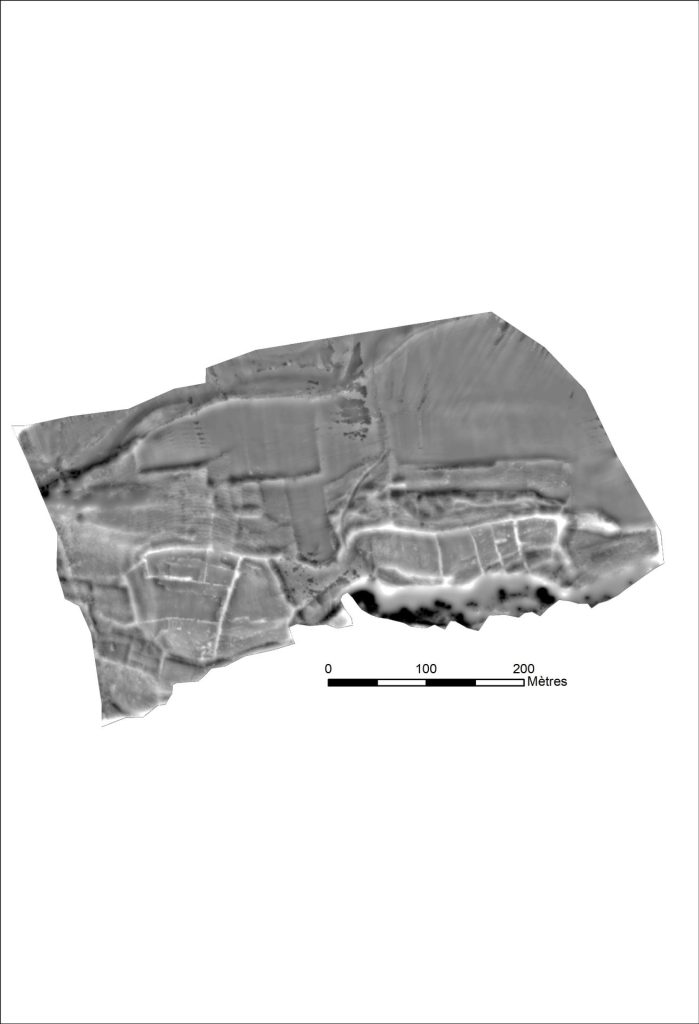

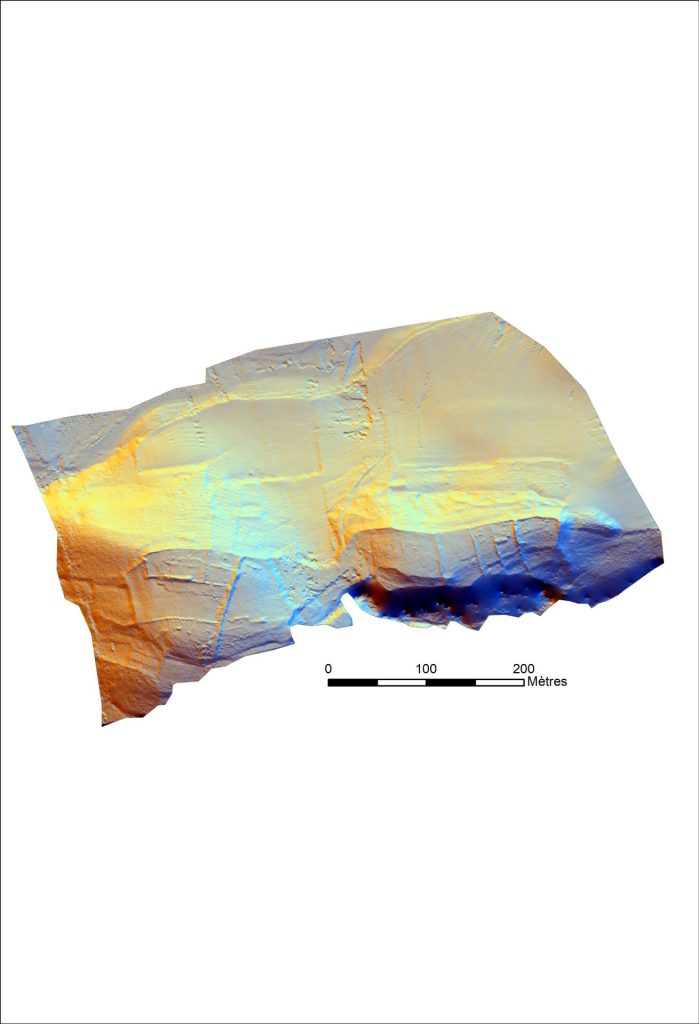

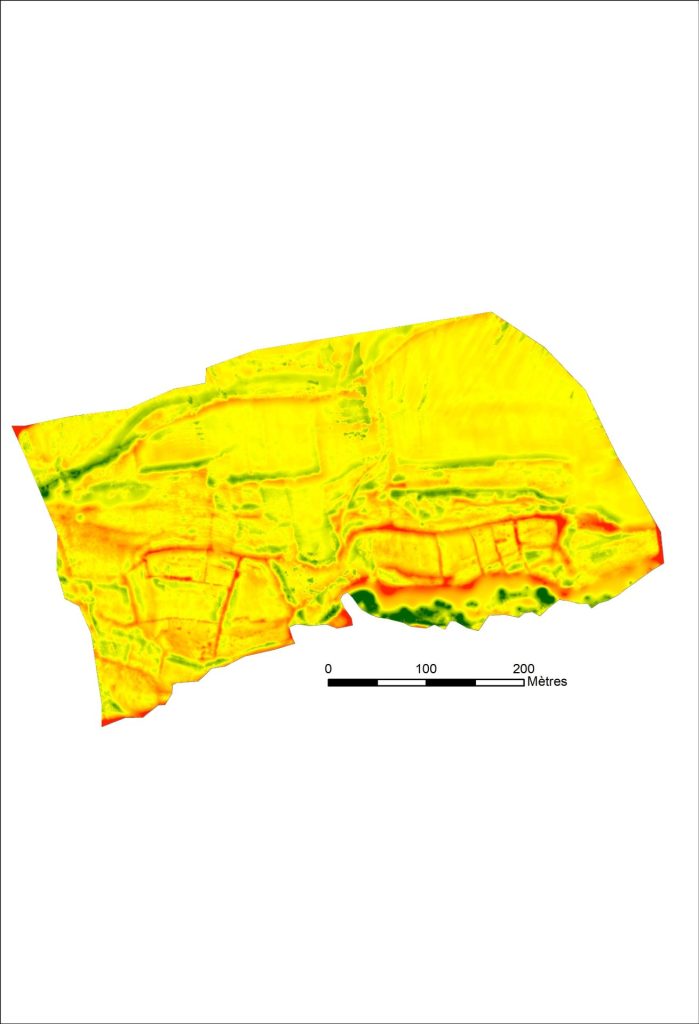

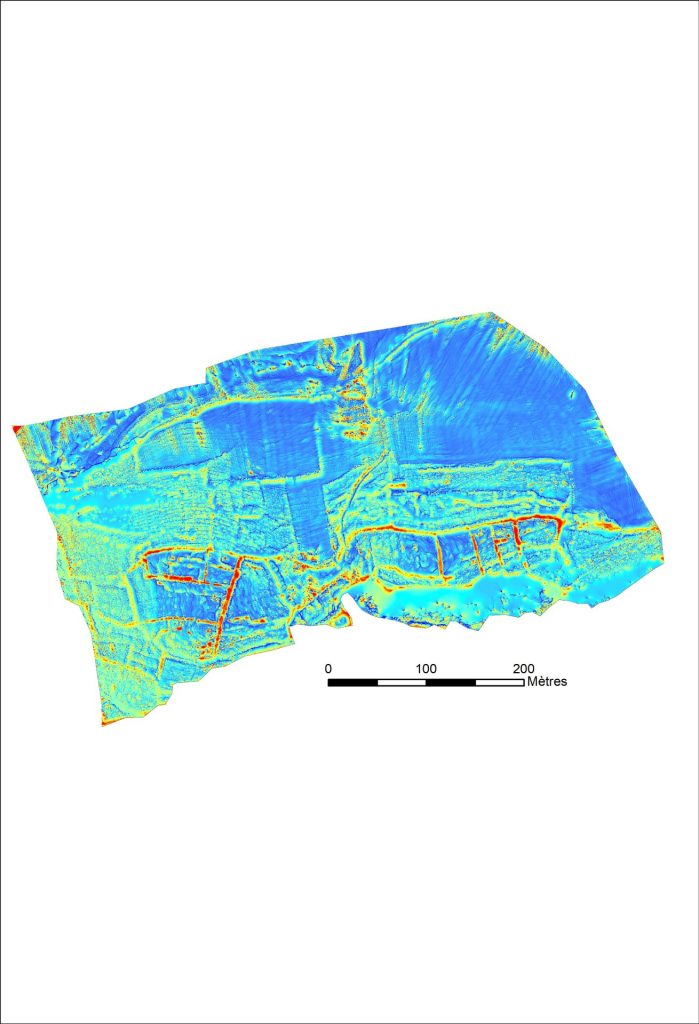

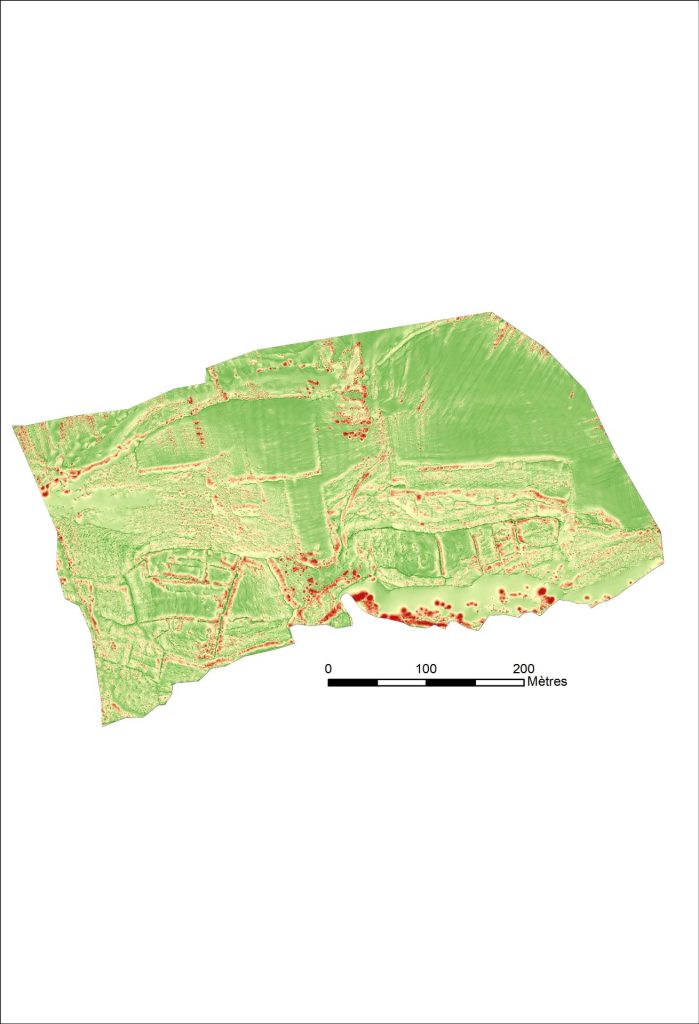

The Digital Elevation Model obtained was reworked with different algorithms to get a first overview of micro-reliefs on surface (with RVT software from Ljubljana Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies)

- hillshading,

- hillshading from multiple directions,

- PCA of hillshading,

- slope gradient,

- simple local relief model,

- sky-view factor,

- anisotropic sky-view factor,

- positive and negative openness.

HillShade H45 D16 DSM

Open POS R10 D16 NetB DSM

Slope 8 bits DSM

SLRM R20 NetB. DSM

Multi Hillshade H45 D16 DSM

SLRM R20 color DSM

Open Neg R10 D16 DSM

Open Pos R10 D16 DSM

Capturing multiple views of the same area allowed for better identification of archaeological indicators, explained Carine Calastrenc, Expert Engineer in Archaeology and non-invasive prospecting new technologies, who was also involved in the project. A first interpretation was done in the ArcGis software and most elements identified were lineaments that could be levelled walls, micro-reliefs or modelled grounds.

Circular or ovoid-shaped clusters of material, called “anomalies”, can also be identified. These may be buried archaeological remains or the presence of low, unfiltered vegetation. Different profiles were then made on a few structures.

YellowScan Mapper 2 and DJI Matrice 600 UAV flying over “L’Escalère” archaeological site – Photo credit. Nicolas Poirier.

YellowScan Mapper 2 and DJI Matrice 600 UAV flying over “L’Escalère” archaeological site – Photo credit. Nicolas Poirier.

This first work allowed Thomas Le Dreff, researcher specialist in History and Archaeology in Metal Ages and Antiquity in Europe, in charge of the operation, to have a first quick overview of the remains present onsite. He then reworked all the data and analyzed it with his specialist’s eye.

The LiDAR models were then compared with the field observations, in particular for certain anomalies that appeared on the survey (linear segments of walls) that had not been spotted during previous visits to the site, which is a dense forest that had not been maintained. Not all the linear results were checked on site, given that some are undoubtedly micro-reliefs that can only be seen on site after a de-vegetation, which could not be done due to lack of time. Numerous small spots visible on the shaded DTM generated seem to correspond to particularly dense areas of vegetation which did not provide ground points here.

Thus, the survey obtained was sufficient for a general reading of the site and to specify the location of the archaeological test pits that were subsequently carried out between late June and early July 2019. This operation had been planned for 6 months and the Lidar survey allowed us to have at our disposal a reliable plan of the site which was impossible to obtain by traditional methods of topographic survey in archaeology (survey with the theodolite or GPS beacon), given the density of the vegetation.

The operation, carried out on 6 small sectors of the site, and in particular at the level of certain stone walls materialized on the Lidar survey, made it possible to specify the morphology of these walls and their dating. This dating was obtained following the highlighting of archaeological layers at the top of which these walls are implanted, the only visible remains of the site before excavation. These archaeological layers yielded fragments of ancient pottery dated to the Iron Age (6th and 2nd/1st centuries BC) or to the modern period (18th-19th centuries).

DEM – Mapper II pointcloud

DSM – Mapper II pointcloud

All this led to the conclusion that most of the walls visible on the surface, thus visible on the Lidar survey, were dated to modern times. They belong to the boundaries of plots intended to contain agricultural or pastoral areas (according to the few historical sources concerning the site, which do not, however, specify the function of this or that plot).

Some massive walls, however, belong to an Iron Age fortification system that very frequently surrounded the hilltop villages (or oppidum) at that time (2 states identified from the pottery fragments as previously indicated: 6th and 2nd/1st centuries BC). These are precisely the results that were assumed from surface collections and sought by coupling this archaeological operation with the LiDAR survey.

L’Escalère site in Saint-Martory (South of France). One of the modern walls visible in the wood. – Photo credit. Thomas Le Dreff.

L’Escalère site in Saint-Martory (South of France). One of the modern walls visible in the wood. – Photo credit. Thomas Le Dreff.

In addition to walls, the LiDAR survey allowed to better draw the plan of important earthworks visible at the edge of the plateau. During the archaeological test pits, these earthworks turned out to be slope breaks that were accentuated by men in the Iron Age. These terraces, which had an external stone facing, perhaps topped by a wooden palisade, allowed, like the massive walls elsewhere on the site, to defend access to the village. These Iron Age features here have collapsed into the slope. This collapse is the result of an ancient (village attacked during the Iron Age?) or relatively recent (levelling of the land to build the boundaries of plots in modern times) voluntary destruction, but also of natural decay.

Using Yellowscan LiDAR system, the archaeologists benefited from easy mission planning, easy access from the road to the survey area and very fast data acquisition and processing. As states Poirier, “A topographical mapping using traditional field methods would have taken several weeks, with low chances of success due to forest cover (poor GPS reception). Here, all worked perfectly !”

Before using YellowScan solution, the research team was doing terrain topography (long, difficult and imprecise) or buying expensive LiDAR data acquired by plane.

“Yellowscan LiDAR solution provided us an easy way to access 3D documentation on unknown archaeological sites hidden under the forest cover. It’s a good solution for small & isolated survey areas which are not big enough to justify the big costs of an airplane LiDAR coverage” says Nicolas Poirier.

NB: Author Julien Bo.